Rich & Blank – A Photo Editor

Marshall Gallery presented “Into the Uncanny Valley which featured three artists: Cody Cobb, Alex Turner and Kaya & Blank. I was confronted with a striking interpretation of something that’s all too familiar on bike rides and commutes along Highway 33 in Ventura county: Pumpjacks.

These dot the hills and neighborhoods between Ventura and Ojai. I caught up with creative duo known as Kaya and Blank about their work.

Heidi: This work revolves around the urban oil fields and refineries in Los Angeles, which image resonates the biggest contrast around consumption and boundary for you?

That might be the image showing a single pump jack in front of a massive container ship in the port of Long Beach. While the pump is stoically working, the global trade system appears in the back. Every time we look at that specific one it gives us a feeling of cause and effect. The same would be true for the frames of pumpjacks with highways or a McDonalds in the background. All of them show the extraction of a resource and the world it creates. There is something very strange about these specific frames.

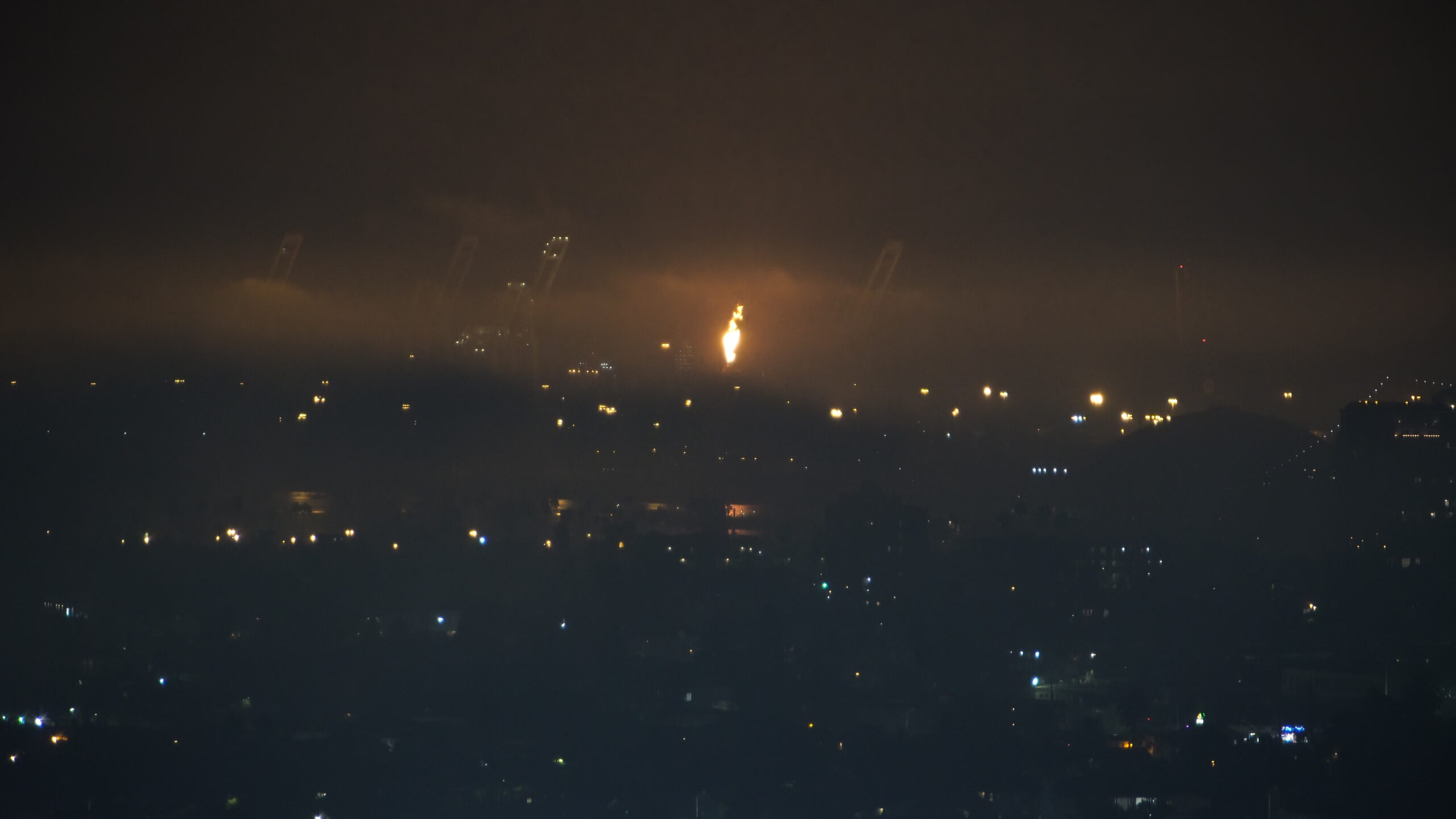

What drew you to nocturnal landscapes?

Işık has always been fascinated by nocturnal landscapes and all her projects created at night, and Thomas has a background in stage performance and theater, so both of us are drawn to dark spaces in which artificial light dominates perception. Something strange and beautiful happens with colors, and modern cameras with extreme low light performance can capture things that are beyond human perception. The sensor amplifies traces of light and the resulting images become somewhat unreal. And then the darkness of course helps to reduce visual noise, it is easier to focus on individual objects in the dark. Furthermore there is this notion that the night is the time to rest, however, capitalism is a 24/7 system. We want to emphasize that in our work.

What are your observations regarding our relationship too crude and how does that unfold in the work?

Although oil plays a massive role in the creation of every product we as humans are surrounded by today and fuels our entire contemporary culture, we never come into direct contact with the raw material itself. It is always already utilized, mediated, transformed, or deliberately concealed. There is very little awareness in the broader public for how essential this one resource is for literally everything and therefore massively informs global politics and especially US politics. But even on a much smaller scale, the local one, it is impressive to see how little people know about Los Angeles as a place of extraction of crude oil. Showing this deep and historical connection is one of the reasons why we show the pump jacks that are basically in the backyards of residential buildings. The detachment from this resource is a huge issue, yet at the same time we as individuals enjoy the comfort that it brings and love exploring the landscape with our cars. Because our own relationship to crude is a complicated one, we want the work to reflect that by being haunting and beautiful at the same time.

The pump jacks take on a zoological aesthetic, how did your framing reinforce that?

Showing mostly individual pump jacks or small groups of them gives a feeling of observing actual characters. Their shape and movement has something inherently animalistic, that’s probably the reason why people also call them nodding donkeys. There is a phenomenon called pareidolia, which describes essentially what happens when we recognize a face in an electrical outlet or a human outline in a cloud. As humans we are prone to see familiar things in random shapes or patterns, which certainly helps to enhance this effect in our videos.

What obstacles did you encounter photographing at night?

Working together certainly helps to feel safer at night, but it’s still a bit scary at times. At least in densely populated areas like Southern California there is no dead of night, there is always something happening, making sounds, crawling around. And that just triggers your imagination. What’s out there? Is it dangerous? The biggest fear at any given moment though was that the police would come and question what we were doing, which happened a few times. Especially in residential areas we would try to be as quick as possible before we would be asked to leave.

How does your collaboration unfold in the field, are you both framing images?

Işık mostly operates the camera while Thomas scouts for different angles or pretends that the engine of our car broke down so we could film from the side of the road. We always discuss framing and decide together how or what to change in a scene, try to refine framing and check for details in the frames together. It is a very fun process and sometimes we dance or do squats while the camera is recording.

What were the determining factors for which areas to photograph?

In 2020 the LA Times published an article with a map by Ryan Menezes and Mark Olalde that shows every single active and idle oil well in California. We used their map to identify clusters in greater Los Angeles that we would work our way through over the course of a night. It was clear relatively quickly that for us the most interesting frames were those that show the extreme proximity of extraction and everyday life and so we focused on clusters in populated areas. However, we did drive out to work in remote oilfields as well, closer to Bakersfield for example, but we ended up never using that material.

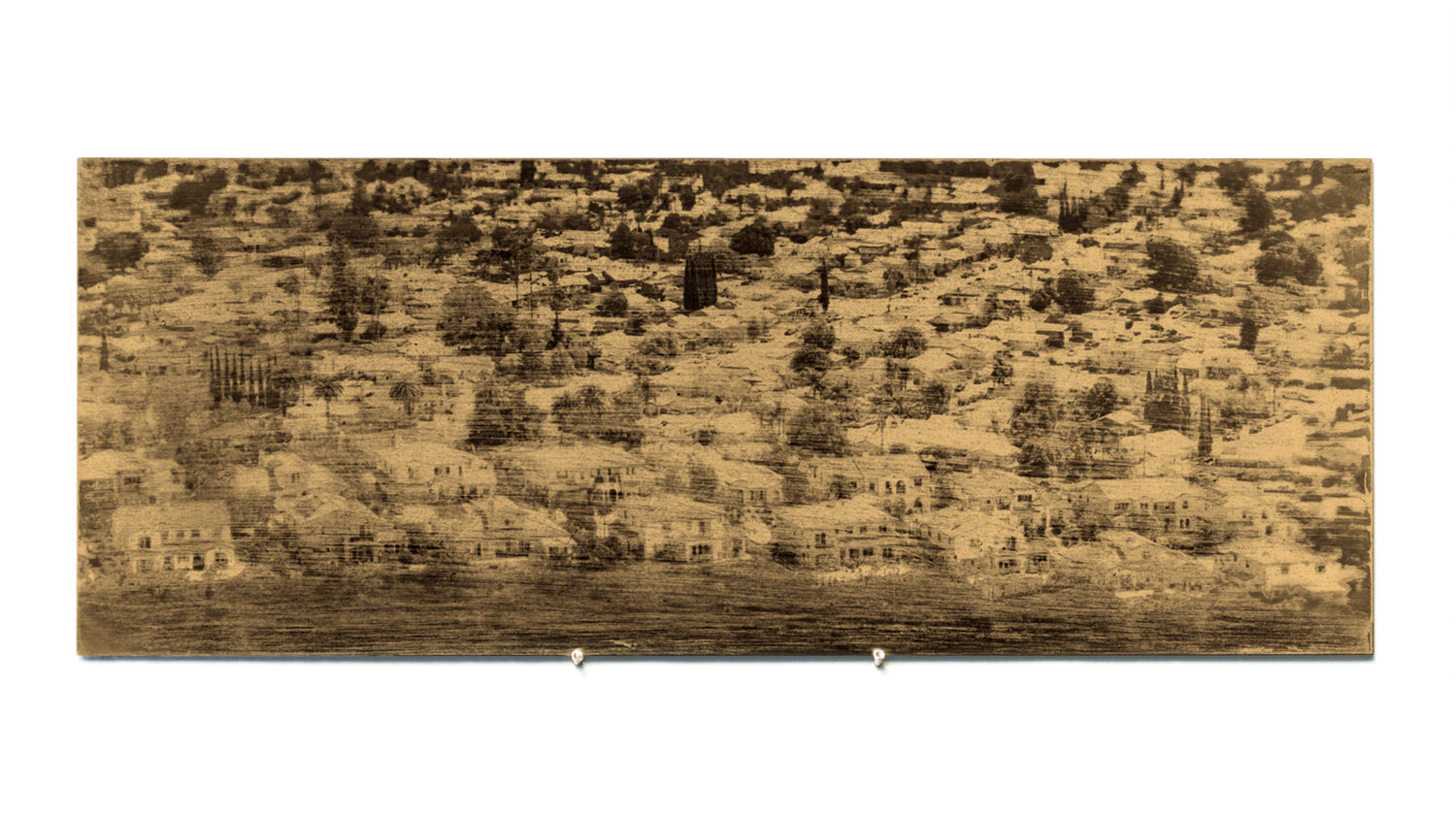

Tell us about the heliographs and why this was important to this body of work.

Crude Aesthetics was created as an installation that addresses the direct connections between visibility, photography, and petroleum. What is known to be the first photograph in history, Joseph Nicéphore Niépce’s View from the Window at Le Gras, was created using bitumen, a naturally occurring petroleum tar which hardens in proportion to its exposure to light. To recreate this historic photographic process, we used tar collected from the La Brea Tar Pits in Los Angeles to print photographs of the USA’s cultural elements that are deeply embedded in excess oil consumption, such as suburbs, drive-throughs, interstate systems, overcrowded parking lots of shopping malls, and Carvana “vehicle vending machines”. Fixing these images with petroleum on a polished, mirror-like aluminum surface allows the viewer to see their own reflection on this raw material and the images of a culture shaped by it.